Archive for the ‘Haas School of Business’ tag

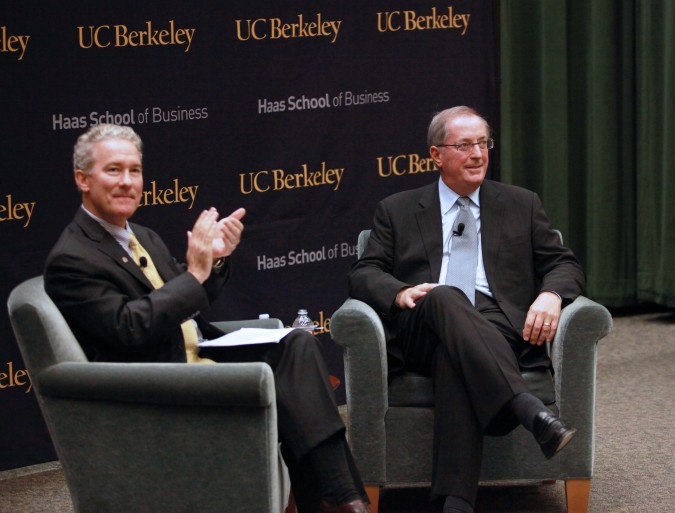

Intel CEO Paul Otellini is interviewed by Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley

Intel CEO Paul Otellini at University of California Berkeley, October 3, 2012. Photograph by Kevin Warnock.

Yesterday afternoon, Wednesday, October 3, 2012, I attended the Dean’s Speaker Series at the Haas School of Business at the University of California Berkeley, in Berkeley, California USA.

Dean Richard Lyons interviewed Paul Otellini, the Chief Executive Officer of Intel Corporation. The question and answer session was held in the Anderson Auditorium, a venue I am very familiar with because it’s the same hall where the Berkeley Entrepreneurs Forum is usually held. I have attended the Forums for 20 years.

The interview was captured by a professional videographer, and the video will be soon made public on the Haas website page for the Speaker Series.

I have highlighted my favorite parts of Otellini’s remarks in my comments that follow.

Haas School of Business student asks Intel CEO Paul Otellini a question October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley

Otellini completed his undergraduate studies at University of San Francisco, and received his Master of Business Administration from the Haas School of Business, though at the time it was named the Berkeley Business School. Otellini got a job at Intel in 1974 with his freshly minted MBA degree. Even though Otellini was a finance specialist, his first job at Intel was to program a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-10 minicomputer to perform cost analysis. This must have been an intense introduction to Intel for an MBA because mini-computers were not easy to program. I programmed a Digital Equipment Corporation VAX minicomputer in 1990, and it was difficult then, so I can only imagine how much more pesky and complicated it was to work 16 years earlier on the ancestor to the VAX.

Audience watches Rich Lyons interview Intel CEO Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley, in Berkeley, California USA

When Otellini became CEO in 2005 he assessed that Intel was not organized correctly for where he saw the market heading. At the time, Intel had 105,000 employees. Otellini eliminated 25,000 jobs. The company is today back up to 103,000 employees. His advisers in 2005 were asking why he wanted to go into ‘the phone business’ when Intel was making money hand over fist at the time. Otelllini said he had many sleepless nights when he was contemplating letting 25,000 people go. He said he will never feel good about that, but he is grateful that he made the change well before the world financial collapse of 2008, so all the people let go were able to find jobs quickly.

Second year Haas student Michael Vladimer asks Intel CEO Paul Otellini a question, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley. To the right of the student, seated: Jill Erbland and Andre Marquis.

I was surprised to learn that Intel is the world’s 4th largest software company in the world based on the number of computer programmers that it employs.

Otellini advised to get work experience in different geographic locations prior to starting a family.

Otellini said its chips are manufactured in three dimensions, which was forced upon it by the laws of physics, which prevented circuits from being made much smaller. To keep making more capable chips, transistors had to be stacked as well as placed side by side. This technology took Intel 10 years to perfect, with thousands of PhD holders working on the effort.

I wonder if they considered adding a ‘Now in 3D!’ tagline to their famous ‘Intel Inside’ stickers.

Audience watches Rich Lyons interview Intel CEO Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley

Otellini emphasized the high risks inherent in running Intel.

To illustrate, when Intel breaks ground on a new chip fabricating factory:

- the technology hasn’t been developed yet

- the products haven’t been designed yet

- the markets for the products don’t exist yet

These factories take 3 1/2 years to build and cost USD $5,500,000,000 each, and Intel starts construction on two or three of these per year.

That sounds like a great definition of high risk to me.

Intel makes hardware reference designs that it provides to its customers so that they can get products to market more rapidly. Otellini said personal computer makers don’t spend that much on industrial design, so they like and need Intel to provide these turn key designs they can modify to make them unique.

Otellini had a mentor at Berkeley while he was a student in the early 1970s. That mentor worked at Bank of America, and tried to get Otellini to join that bank. Several years after Otellini had joined Intel, his mentor confided that Otellini had chosen the right company.

Intel has put in place a system where they can identify the source of so-called conflict minerals. They can also track them, and Otellini said that Intel is likely to be able to say by January 2013 that Intel has built the world’s first ‘conflict mineral free microprocessor’.

Otellini said he had spoken in the morning with Robert Hormats, Under Secretary for Economic, Energy and Agricultural Affairs at the Department of State, who he said is very interested in [removing] conflict minerals from products. The Department of State, according to Otellini, wants to make Intel’s conflict mineral tracking system a so-called ‘best known method’ for the [semiconductor] industry.

Otellini said it recycles the chemicals used in its plants, and plans to recycle the water it uses to such a complete degree that its factories will be able to reuse the water they consume over and over, without needing to return it to the underground aquifers, like they do today.

Audience member at Dean's Speaker Series with Paul Otellini at Haas School of Business, October 3, 2012.

Otellini spoke about manufacturing competitiveness generally in the United States, something he is qualified to speak about because he advises United States President Barack Obama about competitiveness.

He said many of the motivating factors that have led to outsourcing are disappearing. He said that it costs more for Intel to hire 1st and 2nd level technical managers in China now than it does in Santa Clara, California USA. For engineers with 3 or 4 years of experience, the costs to hire them are now the same in the US as they are in China and India.

Otellini said that the United States could improve its position by lowering its corporate tax rate [to a level consistent with the rate in competitive economies]. He suggested the US streamline its permitting procedures for building new factories. He suggested that job training be improved to provide a skilled workforce to work in the new factories. He pointed out that currency and political risks are low in the US, and stated there is no risk of a company’s factory being expropriated by the US government. In other countries, governments sometimes do take over privately owned factories.

Paul Otellini speaks with Arthur Gensler at University of California Berkeley, October 3, 2012. Photograph by Kevin Warnock.

There were some famous guests in the audience.

Perhaps the most famous attendee was Arthur Gensler, the founder of M. Arthur Gensler Jr. & Associates, Inc. but commonly referred to as simply Gensler. I have been aware of this global architecture, planning, design and consulting firm since I was 23 years old at my first job out of college, at Newell Color Laboratory at 630 Third Street in San Francisco, California USA, since closed. Gensler was an important client. I suspect Gensler may be helping to design the new building Dean Lyons is being planned for the Haas School of Business campus.

Arthur Gensler speaking with Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at Haas School of Business at University of California Berkeley

After the interview, Lyons pointed out Mr. Gensler to me — without his helpful comment, I would not have been able to write this acknowledgment of his visit. Gensler is a big deal — they employ 3,500 people in 42 locations. They count all 10 of the Fortune 500 top 10 companies as clients.

Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons, left, watches Haas Professor Emeritus and Nobel Prize winner Oliver Williamson shake hands with Intel CEO Paul Otellini at Haas School of Business at University of California Berkeley, October 3, 2012. Photograph by Kevin Warnock.

Perhaps the second most famous attendee was Oliver Williamson. Williamson is Professor Emeritus at the Haas School of Business. In 2009 Williamson won the Nobel Prize for Economics. I saw Williamson speak in 2009 at the Haas Gala, the annual party the school throws each November. I blogged about that gala and wrote about Williamson, who spoke at the event. I took a picture of Williamson shaking hands with Otellini, shown here.

Intel CEO Paul Otellini with University of California Berkeley student Tammie Chen. Photograph by Kevin Warnock, October 3, 2012.

This last photograph of Mr. Otellini with Berkeley undergrad student Tammie Chen has an interesting story behind it.

I met Chen when she was an organizer for the 2011 Made for China Startup Pitch Competition. I was a judge for that competition. After that event, we became friends on Facebook, and she posted that she was going to be attending the Dean’s Speaker Series that is the subject of this blog post. I commented that I would be there as well, blogging. She asked me if I could take a picture of her with Otellini. I said I would. I walked up to him and asked him if I could introduce Chen to him and take a picture of him with her, and he readily agreed. They had a nice chat for a minute, and then they posed for this picture. Chen is a huge fan of Intel, and has visited their headquarters. She has a lot of friends that work at Intel.

I was surprised that no students approached Otellini to introduce themselves. This is the same behavior I saw at my first Dean’s Speaker Series event, in September 2012, when Lyons interviewed Randall Stephenson, the CEO of AT&T. There were students standing about 10 feet away from Otellini, in a large circle, but not a single student walked into the empty space to say hello. That made it easy for me to say hello to Mr. Otellini, who I have met and spoken with before, in 2008, at the Intel Capital CEO Summit [renamed the Intel Capital Global Summit] in San Francisco.

Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons and Intel CEO Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley. Photo by Kevin Warnock.

I like Intel. Their venture capital division Intel Capital was very nice to my company Silveroffice, Inc. by making it an Intel Capital Portfolio Company. Intel Capital invites me as their guest to Intel’s annual Intel Developer Forum, at which I get a new Intel Developer Forum branded laptop bag or backpack, which I use every time I leave my home with my Intel powered laptop. I hope to be appointed a judge for the Intel Global Challenge, a role I would be great at since I was a judge for the Berkeley Startup Competition for eight years through 2011. My application is pending, so please wish me luck! I love judging startup competitions, and so far I have judged four different competitions at University of California Berkeley.

I took all the photographs in this post. I used a Canon 5D Mark II camera with a Canon 80-200mm f:2.8 L zoom lens. Click on the images twice in delayed succession to see the images at full size. I uploaded the images at their full 21 megapixel resolution, at a JPG quality of 12. The light level was comparatively low, so I shot at ISO 2,500, without flash.

Thank you to Meg Fellner of the Dean’s Office for getting me a ticket to this sold out event.

Have an MBA and an idea? Looking for a technical co-founder to build it and join your unfunded startup for equity alone?

One of my highlights each month is serving as a mentor for the Haas Founders group.

Haas Founders is a group for Haas School of Business graduates from the University of California at Berkeley. It’s an invitation only group, but if you graduated from Haas you are quite likely to receive an invitation if you are a founder or co-founder of a startup company.

Another way in is to have a meaningful connection to the Haas School. That’s how I became a member. I have been a judge for the Berkeley Startup Competition from about 2004 through 2011.

Finally, all Haas graduates can buy their way in by agreeing to pay for the food and drinks. This allows service providers like bankers, investors and accountants to attend. Such service providers can meet ambitious startup founders that sometimes turn into clients.

I write the above to introduce you to the Haas Founders meeting. There is a Facebook page and a Twitter account for Haas Founders. Michael Berolzheimer moderates and organizes the Haas Founders meetings. Berolzheimer runs the genesis-stage venture firm Bee Partners which, according to his firm’s web site, pollinates visionary entrepreneurs with financial, human and social capital. Kishore Lakshminarayanan helps Berolzheimer set up the meetings, which take place at different venues each month, in the East Bay, South Bay and San Francisco, California USA. I met Berolzheimer in 2007, before he took on the responsibility for Haas Founders from the previous organizer, Mat Fogarty, CEO of Crowdcast.

Haas Founders has established a group on the professional social networking site Linked In. As of this morning there are 86 members. I believe the group is seeking new members, so if you fit the requirements, please introduce yourself to Michael Berolzheimer.

Haas Founders can be thought of as a board of directors like support group for startup founders, where no issues are off limits for discussion. That makes Haas Founders one of the most compelling meetings I’ve had the good fortune to attend.

I have attended the Haas Founders meetings since about 2005. Individual meetings are limited to 20 attendees.

This open forum for frank talk is made possible because attendees are asked to keep the the conversations confidential. To my knowledge, there has never been a meaningful breach of this rule. I think that’s a reflection of the trustworthiness and integrity of Haas students and graduates.

Given this secrecy, how can I write a blog post about Haas Founders?

Well, I am not going to discuss confidential information. The advice I am going to give is my own. I gave this advice to a participant at the most recent meeting March 6, 2012 in San Francisco.

I am not breaking confidentiality by repeating what I said that day because I have given this same advice many times without any restriction of confidentiality. It’s already public information. Problem averted. I ran this post by Berolzheimer before publishing it, as I want to be extra careful so as to not be uninvited to future meetings.

I decided to write this post because the issue I am going to talk about comes up so frequently that I have spent hours and hours answering this question over the years.

The question and answer are as follows:

Q: I am a non-technical founder and I have thought of a business idea that requires something technical be built. How do I find a talented technical co-founder to join my company for equity only to build my vision for me?

A: Forget it!

You can’t find a talented technical co-founder to join your unfunded idea stage company for equity only.

There are rare exceptions, but you can not count on them and should not consider counting on them.

One solution is to think of and pursue a business idea that you can implement with only the skills you have already. Here are three companies that I suspect began with little computer programming, for example:

- Become a mushroom farmer.

- Start a fair trade import company.

- Start a men’s fashion manufacturing company.

The smart people I suggest this answer to don’t quickly embrace my advice. That’s understandable. They are in love with their vision and they want to pursue that vision right now. They don’t want to hunt for a technically simpler business idea. They don’t want to learn the technical skills necessary to develop their original idea. They want a savior, a Steve Wozniak, to fall from the sky to do the real work of making a viable product. Usually such non-technical founders also want to reserve more of the company equity for themselves than for this savior, because they thought of the idea. If there is to be an equity disparity, I suggest it be weighted toward the technical contributors who make the product happen, not the non-technical people who think up the idea.

What non technical founders fail to appreciate is that talented technical individuals with the grit to want to start a company are in high demand. They are like supermodels in their desireability. A lot of people are asking them for dates. A lot of these suitors have lots of money to woo them with.

Why would a supermodel date a founder with no money when there is a line of suitors with six, seven or eight figure stacks of money at their side ready to spend?

The answer is supermodels don’t date broke founders.

Supermodels don’t hook up with unfunded MBAs that have a cool idea.

The perhaps sad truth is that MBAs are not held in high regard by many technical experts. This is not a comment on Berkeley MBAs, but on all MBAs. Of course, technical experts desperately need business experts at some point, as exits are rare for companies filled with only technical experts. I am not taking a stand on which type of person is more valuable because they are both vital. What I am saying is the technical people generally perceive that MBAs are not that important. If that’s the perception, then how can an MBA recruit a technical person without money?

There are millions of cool ideas to pursue at any moment. That’s always been the case and that will always be the case.

Talented technical people know they are in demand. They have recruiters calling them telling them so all the time. They read TechCrunch, VentureBeat and GigaOm. They know the technology world is in the middle of a full fledged boom right now. So only 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th rate technical people will agree to an equity only founder position with a non-technical sole co-founder.

The only practical exception is if you’ve already been friends with the person for years and they know your work and respect it. So classmates graduating together can get together and start a company, with some founders being non technical and some being technical.

But if you’re looking for a stranger to drop out of the sky to build your vision, you should forget it and focus on finding a simpler idea or on learning the technical skills yourself so you can build the first version of the product by yourself.

Yes, the product won’t likely have to polish of one created by a more seasoned expert, but it can be good enough. You only need it to be good enough to raise money that you can then use to pay a more skilled technical person to make an improved version.

I am not spouting off advice I read somewhere or heard somewhere — I know what I am talking about. Pardon me while I now go into extreme detail to convince you that I do know what I am talking about. What follows may seem like too much, but I have spent dozens and dozens of hours trying to beat this lesson into the heads of very smart non-technical company founders. I feel I need to pull out all the stops here to convince the skeptical that I am right.

I know it’s smart to learn to program because this is what I did to take my startup Hotpaper.com, Inc. from a USD $10,000 investment when I had almost no applicable skills through to a USD $10,000,000+ sale to a public company just six years later.

This is news I’ve written about more than once. But I haven’t described the grueling early work I put in that made this ‘quick success’ possible.

When I started Hotpaper, I was a minicomputer programmer. A Digital Equipment Coporation VAX minicomputer running Open VMS. There was nothing miniature about this computer. It filled an entire raised-floor water-cooled computer room and served 1,000 users in five offices in two US states. I believe it cost more than USD $12,000,000. Back then a 9 gigabyte disk drive cost USD $250,000. I saw the invoices and recall calculating the price per gigabyte.

When I started Hotpaper my only experience programming a PC was writing rudimentary DOS batch files. One can still write these for Windows, to run at a command window prompt. You can do amazing things with batch files, but you can’t write serious client-server or web applications with them. I had to learn to program graphical Microsoft Windows applications, and I had only used DOS on a PC up until that point. I had played for a few hours with a copy of Windows 3.1, but that was the extent of my experience with Windows. The one machine my employer had that ran Windows was so slow (Intel 386 with perhaps 1 megabyte of memory) that when you pressed a letter in a word processor (Ami Pro), there was a lag of about 1 full second before the character would show up on screen. It was pathetic.

I immediately bought a Hewlett Packard Pentium 60 Mhz computer with 4 megabytes of RAM and Windows 3.1 for Workgroups. I added Microsoft Office, which came on 30+ 3 1/2″ floppy disks, not a CD-ROM. This was a Pentium, not a Pentium II, III or IV. In fact, it was the slowest Pentium chip ever sold. But this was the fastest computer I had ever used. I still have it, in storage.

I all but shut myself off from the world for two years with hundreds of dollars of technical books, a 28.8K modem and a telephone. I taught myself to be an event driven computer programmer. Event driven programming is much different from the procedural programming I had done to program the huge VAX system run by my employer at the time, Cooley LLP. Yes, I knew how to program a little bit on a VAX, but Windows is so different that it’s almost as if I was learning to program from scratch.

Thankfully, Microsoft was not yet the market leader in word processing in 1994 since WordPerfect for DOS still dominated, so Microsoft tried very hard to persuade developers to embrace their Word word processing software. They offered free telephone technical support for programming problems, provided you paid for the phone call. There were no unlimited business phone lines back then, so my office phone bill was perhaps USD $100 a month due to all my calls to Microsoft — hours and hours of calls per month. I owe Microsoft so much for those calls, as they helped me to solve every problem I ever encountered. Thank you Microsoft.

Eventually Microsoft overnight switched from free technical support calls to USD $55.00 per incident technical support calls, and I had to stop calling them. But that was a couple of years later, and I had already gotten to be proficient by then, and I could get my questions answered for free on their well run newsgroups. By that point, Word and Office were the market leaders, and they didn’t need to try so hard to make developers embrace their tools.

I worked hard — really, really hard. I worked from about 10am to 10pm Monday through Saturday. On Sunday I wouldn’t come into the office until the mid afternoon, but I would still stay until 10pm or so. I did this from January 1995 through the end of 1996 or so, I believe. It took me that long to learn Windows programming reasonably well.

I didn’t know other software developers. There were no popular coworking spaces. Meetup didn’t exist. I was shy. But I was driven… really, powerfully and passionately driven. I had so little money I was living in a tiny studio apartment on Mason Street near Bush Street in San Francisco, California USA. My rent was USD $625 a month including utilities. I only owned one computer, so I could not work at home. I was at the office a lot, and it was just a seven minute walk to get there. I became really good friends with my office mates the late Stan Pasternak and patent attorney Robert Hill. I have such fond memories of that time.

Was the code I produced great? No. Was it awful? No. Was it reliable? Yes. Was it understandable to others? Yes. Did it get used by others for meaningful projects? Yes. Did I raise money with it? Yes. Did I sell the company successfully by following this model? Yes. Can you do the same? I think so.

At Hotpaper, I had a customer from the day I bought a computer. I told them I could build what they asked for. I actually had never done so on Windows. I had to figure out how to program Windows because I had a paying customer that demanded a Windows client-server based solution. They were paying me thousands so I had to deliver. I didn’t study for two years and then start to look for a client. I got the client based on my past reputation as a VAX programmer and then faked it until I made it.

It turns out that first project failed and the client never used my work or the work of any custom software developer.

They just bought an off the shelf application and conformed to its way of doing things.

But that’s irrelevant in the end. I got paid USD $30,000. I worked hard. The client made the best decision, for they should never have hired me or any developer when an off the shelf package was available for much less than having custom software written. I learned a lot, kept the rights to what I had built but did not get used, and I used that for the basis for what I then turned around and sold to Coca-Cola and the United States Department of Commerce, where it did get used on an enterprise scale.

Today it’s easier than ever to become a programmer. There are so many online tutorials like those from Codecademy. There are so many hacker co-working spaces like Hacker Dojo where you can base your new venture. You can work there as many hours as you can keep your eyes open, and there are smart people around much of the time to get help from.

Today all the software you need to do almost any project is free. That wasn’t the case in 1995, when now standard building blocks like MySQL hadn’t been popularized yet.

I have seen smart graduates spin their wheels for months or years trying to recruit a magical co-founder to build their product. How much better it would be for these people to sit down at Hacker Dojo and focus their considerable brain power on learning to program software directly. Even if the entire result is eventually rewritten later by someone more skilled, they would be better off than if they somehow found the mythical co-founder.

For once you know how to program in any language, you will be able to talk about and think about technical problems far more effectively than you can as a non programmer. It will be far more difficult for people to confuse, mislead or bamboozle you. You will be able to hire better programmers who will respect you more. You will be able to tell programmers what to attempt with more clarity and conviction because you know at least something about their world.

You will have insight into a world that’s richly diverse and totally fascinating. Your life will improve even if you never make a penny from your venture.

Programming is not easy. It can be absurdly complicated and exasperating at times. That’s why new college graduates who know little about the real world of programming can still command pay approaching USD $100,000 to start.

I am just one modestly successful entrepreneur.

Before you become a programmer, ask some technical startup founders you trust and see if they agree with what I’ve written here. Remember, Steve Jobs got lucky with Steve Wozniak. Silicon Valley was a sleepy place back then compared to today. Go make your own luck by developing your technical skills. If you have an MBA, you presumably spent four years to get an undergraduate degree and two years to get a business degree. Spend two more years to become a programmer. Doctors spend more time studying before they complete their education, so view eight years of study as normal, not crazy or silly.

I love programming, and I am extremely grateful I spent those grueling early years just powering through the books and road blocks to learn to program.

I feel I can do nearly anything I can dream up.

That’s a powerful feeling I wouldn’t give up for anything.

Please subscribe to this blog by leaving your email address in the upper right corner. Please friend or subscribe to me on Facebook. Please follow me on Twitter.

Occupy Cal protest at University of California at Berkeley November 15, 2011

I was at the Occupy Cal protest at University of California at Berkeley last evening, November 15, 2011. There were over 1,000 protesters there. The energy in the air was positive and infectious.

As far as I could detect, the Occupy Cal event wasn’t marred by the shooting of a Berkeley student by campus police earlier in the afternoon. That student later died at the hospital. That student, Christopher Nathen Elliot Travis, age 32, was a transfer student from Ohlone College in Fremont, California.

Haas School of Business Dean Richard Lyons addressed the school’s students this morning. Later, Lyons posted this letter to the Haas Newsroom and publicized it via the micro-blogging website Twitter.

My friend Heather Sepulveda went to Ohlone College before she transferred to UC Berkeley years ago — a very strange coincidence to be sure.

There was a drum beat to the protest, thanks to the talented musicians that showed up. One of the musicians looked to be about 60, and he said he had participated in the anti war protests at UC Berkeley in the 1960s. I feature some of the music in the video I am editing from the event, which I hope to post tomorrow. I got some great video, including of the camping tents being carried into place.

Board member of the Mario Savio Lecture Fund addressing Occupy Cal protesters November 15, 2011 at Sproul Plaza

The event incorporated a gathering of The Savio Lecture Fund, which originally was to take place indoors at the Pauley Ballroom in the Martin Luther King Jr. Student Center, also on the UC Berkeley campus. My guess is the change of venue was decided close to the last minute to benefit from the association with the Occupy Cal movement. I was not previously familiar with Mario Savio, I am embarrassed to admit. I concluded from the talks I heard last night that Savio would have embraced the Occupy Cal movement and message. Savio spoke on December 2, 1964 from the same steps of Sproul Hall where the speakers last night spoke from.

The Savio Lecture speaker last evening was former United States Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, who is a Professor of Public Policy at UC Berkeley. I captured his speech to high definition video and presented it on my blog earlier today.

In the photograph above you can see some of the camping tents already in place, along with another tent being carried into place already set up. Organizers were distributing hot food on the Sproul Hall steps. Even though there were a lot of people there, it was possible to easily move among the crowd, and I had no trouble taking pictures and video, even though I had brought a tripod with me, for many of the time exposures I took to capture the low light images you see here.

Soap bubbles by the hundreds liven up the view from the steps of Sproul Hall during Occupy Cal protest at UC Berkeley November 15, 2011

I took the above shot right before I departed, after 10pm. The group front and center appeared to be in their 50s and 60s. The age mix of the crowd was inspiring — it definitely wasn’t just current students in their teens and twenties. I felt that people were really passionate about the Occupy movement, and that this movement will be long lived and will accomplish real change in the world. I am glad I made the trip from San Francisco.

I uploaded these pictures at full 21 megapixel resolution. To see them at full size, click on them twice, with a pause in between the clicks to allow the photographs to load in a separate window. If you’d like to use these pictures for something, please give me a link back to my blog. If you like this blog, please subscribe, and please add this post to your status feed on Facebook. Thank you!