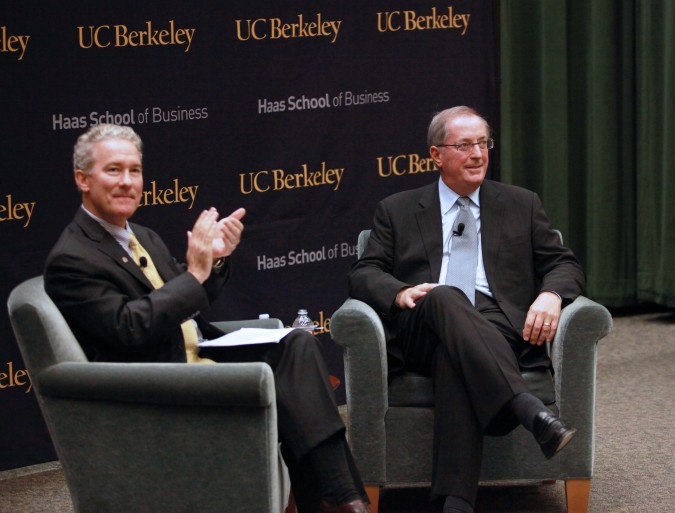

Intel CEO Paul Otellini is interviewed by Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley

Intel CEO Paul Otellini at University of California Berkeley, October 3, 2012. Photograph by Kevin Warnock.

Yesterday afternoon, Wednesday, October 3, 2012, I attended the Dean’s Speaker Series at the Haas School of Business at the University of California Berkeley, in Berkeley, California USA.

Dean Richard Lyons interviewed Paul Otellini, the Chief Executive Officer of Intel Corporation. The question and answer session was held in the Anderson Auditorium, a venue I am very familiar with because it’s the same hall where the Berkeley Entrepreneurs Forum is usually held. I have attended the Forums for 20 years.

The interview was captured by a professional videographer, and the video will be soon made public on the Haas website page for the Speaker Series.

I have highlighted my favorite parts of Otellini’s remarks in my comments that follow.

Haas School of Business student asks Intel CEO Paul Otellini a question October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley

Otellini completed his undergraduate studies at University of San Francisco, and received his Master of Business Administration from the Haas School of Business, though at the time it was named the Berkeley Business School. Otellini got a job at Intel in 1974 with his freshly minted MBA degree. Even though Otellini was a finance specialist, his first job at Intel was to program a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-10 minicomputer to perform cost analysis. This must have been an intense introduction to Intel for an MBA because mini-computers were not easy to program. I programmed a Digital Equipment Corporation VAX minicomputer in 1990, and it was difficult then, so I can only imagine how much more pesky and complicated it was to work 16 years earlier on the ancestor to the VAX.

Audience watches Rich Lyons interview Intel CEO Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley, in Berkeley, California USA

When Otellini became CEO in 2005 he assessed that Intel was not organized correctly for where he saw the market heading. At the time, Intel had 105,000 employees. Otellini eliminated 25,000 jobs. The company is today back up to 103,000 employees. His advisers in 2005 were asking why he wanted to go into ‘the phone business’ when Intel was making money hand over fist at the time. Otelllini said he had many sleepless nights when he was contemplating letting 25,000 people go. He said he will never feel good about that, but he is grateful that he made the change well before the world financial collapse of 2008, so all the people let go were able to find jobs quickly.

Second year Haas student Michael Vladimer asks Intel CEO Paul Otellini a question, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley. To the right of the student, seated: Jill Erbland and Andre Marquis.

I was surprised to learn that Intel is the world’s 4th largest software company in the world based on the number of computer programmers that it employs.

Otellini advised to get work experience in different geographic locations prior to starting a family.

Otellini said its chips are manufactured in three dimensions, which was forced upon it by the laws of physics, which prevented circuits from being made much smaller. To keep making more capable chips, transistors had to be stacked as well as placed side by side. This technology took Intel 10 years to perfect, with thousands of PhD holders working on the effort.

I wonder if they considered adding a ‘Now in 3D!’ tagline to their famous ‘Intel Inside’ stickers.

Audience watches Rich Lyons interview Intel CEO Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley

Otellini emphasized the high risks inherent in running Intel.

To illustrate, when Intel breaks ground on a new chip fabricating factory:

- the technology hasn’t been developed yet

- the products haven’t been designed yet

- the markets for the products don’t exist yet

These factories take 3 1/2 years to build and cost USD $5,500,000,000 each, and Intel starts construction on two or three of these per year.

That sounds like a great definition of high risk to me.

Intel makes hardware reference designs that it provides to its customers so that they can get products to market more rapidly. Otellini said personal computer makers don’t spend that much on industrial design, so they like and need Intel to provide these turn key designs they can modify to make them unique.

Otellini had a mentor at Berkeley while he was a student in the early 1970s. That mentor worked at Bank of America, and tried to get Otellini to join that bank. Several years after Otellini had joined Intel, his mentor confided that Otellini had chosen the right company.

Intel has put in place a system where they can identify the source of so-called conflict minerals. They can also track them, and Otellini said that Intel is likely to be able to say by January 2013 that Intel has built the world’s first ‘conflict mineral free microprocessor’.

Otellini said he had spoken in the morning with Robert Hormats, Under Secretary for Economic, Energy and Agricultural Affairs at the Department of State, who he said is very interested in [removing] conflict minerals from products. The Department of State, according to Otellini, wants to make Intel’s conflict mineral tracking system a so-called ‘best known method’ for the [semiconductor] industry.

Otellini said it recycles the chemicals used in its plants, and plans to recycle the water it uses to such a complete degree that its factories will be able to reuse the water they consume over and over, without needing to return it to the underground aquifers, like they do today.

Audience member at Dean's Speaker Series with Paul Otellini at Haas School of Business, October 3, 2012.

Otellini spoke about manufacturing competitiveness generally in the United States, something he is qualified to speak about because he advises United States President Barack Obama about competitiveness.

He said many of the motivating factors that have led to outsourcing are disappearing. He said that it costs more for Intel to hire 1st and 2nd level technical managers in China now than it does in Santa Clara, California USA. For engineers with 3 or 4 years of experience, the costs to hire them are now the same in the US as they are in China and India.

Otellini said that the United States could improve its position by lowering its corporate tax rate [to a level consistent with the rate in competitive economies]. He suggested the US streamline its permitting procedures for building new factories. He suggested that job training be improved to provide a skilled workforce to work in the new factories. He pointed out that currency and political risks are low in the US, and stated there is no risk of a company’s factory being expropriated by the US government. In other countries, governments sometimes do take over privately owned factories.

Paul Otellini speaks with Arthur Gensler at University of California Berkeley, October 3, 2012. Photograph by Kevin Warnock.

There were some famous guests in the audience.

Perhaps the most famous attendee was Arthur Gensler, the founder of M. Arthur Gensler Jr. & Associates, Inc. but commonly referred to as simply Gensler. I have been aware of this global architecture, planning, design and consulting firm since I was 23 years old at my first job out of college, at Newell Color Laboratory at 630 Third Street in San Francisco, California USA, since closed. Gensler was an important client. I suspect Gensler may be helping to design the new building Dean Lyons is being planned for the Haas School of Business campus.

Arthur Gensler speaking with Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at Haas School of Business at University of California Berkeley

After the interview, Lyons pointed out Mr. Gensler to me — without his helpful comment, I would not have been able to write this acknowledgment of his visit. Gensler is a big deal — they employ 3,500 people in 42 locations. They count all 10 of the Fortune 500 top 10 companies as clients.

Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons, left, watches Haas Professor Emeritus and Nobel Prize winner Oliver Williamson shake hands with Intel CEO Paul Otellini at Haas School of Business at University of California Berkeley, October 3, 2012. Photograph by Kevin Warnock.

Perhaps the second most famous attendee was Oliver Williamson. Williamson is Professor Emeritus at the Haas School of Business. In 2009 Williamson won the Nobel Prize for Economics. I saw Williamson speak in 2009 at the Haas Gala, the annual party the school throws each November. I blogged about that gala and wrote about Williamson, who spoke at the event. I took a picture of Williamson shaking hands with Otellini, shown here.

Intel CEO Paul Otellini with University of California Berkeley student Tammie Chen. Photograph by Kevin Warnock, October 3, 2012.

This last photograph of Mr. Otellini with Berkeley undergrad student Tammie Chen has an interesting story behind it.

I met Chen when she was an organizer for the 2011 Made for China Startup Pitch Competition. I was a judge for that competition. After that event, we became friends on Facebook, and she posted that she was going to be attending the Dean’s Speaker Series that is the subject of this blog post. I commented that I would be there as well, blogging. She asked me if I could take a picture of her with Otellini. I said I would. I walked up to him and asked him if I could introduce Chen to him and take a picture of him with her, and he readily agreed. They had a nice chat for a minute, and then they posed for this picture. Chen is a huge fan of Intel, and has visited their headquarters. She has a lot of friends that work at Intel.

I was surprised that no students approached Otellini to introduce themselves. This is the same behavior I saw at my first Dean’s Speaker Series event, in September 2012, when Lyons interviewed Randall Stephenson, the CEO of AT&T. There were students standing about 10 feet away from Otellini, in a large circle, but not a single student walked into the empty space to say hello. That made it easy for me to say hello to Mr. Otellini, who I have met and spoken with before, in 2008, at the Intel Capital CEO Summit [renamed the Intel Capital Global Summit] in San Francisco.

Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons and Intel CEO Paul Otellini, October 3, 2012 at University of California Berkeley. Photo by Kevin Warnock.

I like Intel. Their venture capital division Intel Capital was very nice to my company Silveroffice, Inc. by making it an Intel Capital Portfolio Company. Intel Capital invites me as their guest to Intel’s annual Intel Developer Forum, at which I get a new Intel Developer Forum branded laptop bag or backpack, which I use every time I leave my home with my Intel powered laptop. I hope to be appointed a judge for the Intel Global Challenge, a role I would be great at since I was a judge for the Berkeley Startup Competition for eight years through 2011. My application is pending, so please wish me luck! I love judging startup competitions, and so far I have judged four different competitions at University of California Berkeley.

I took all the photographs in this post. I used a Canon 5D Mark II camera with a Canon 80-200mm f:2.8 L zoom lens. Click on the images twice in delayed succession to see the images at full size. I uploaded the images at their full 21 megapixel resolution, at a JPG quality of 12. The light level was comparatively low, so I shot at ISO 2,500, without flash.

Thank you to Meg Fellner of the Dean’s Office for getting me a ticket to this sold out event.